Assurance: where does the pyramid point?

08 September 2023

In the third of his series of articles about public sector assurance, GGI CEO Andrew Corbett-Nolan sets out what’s required to secure assurance in large complex organisations.

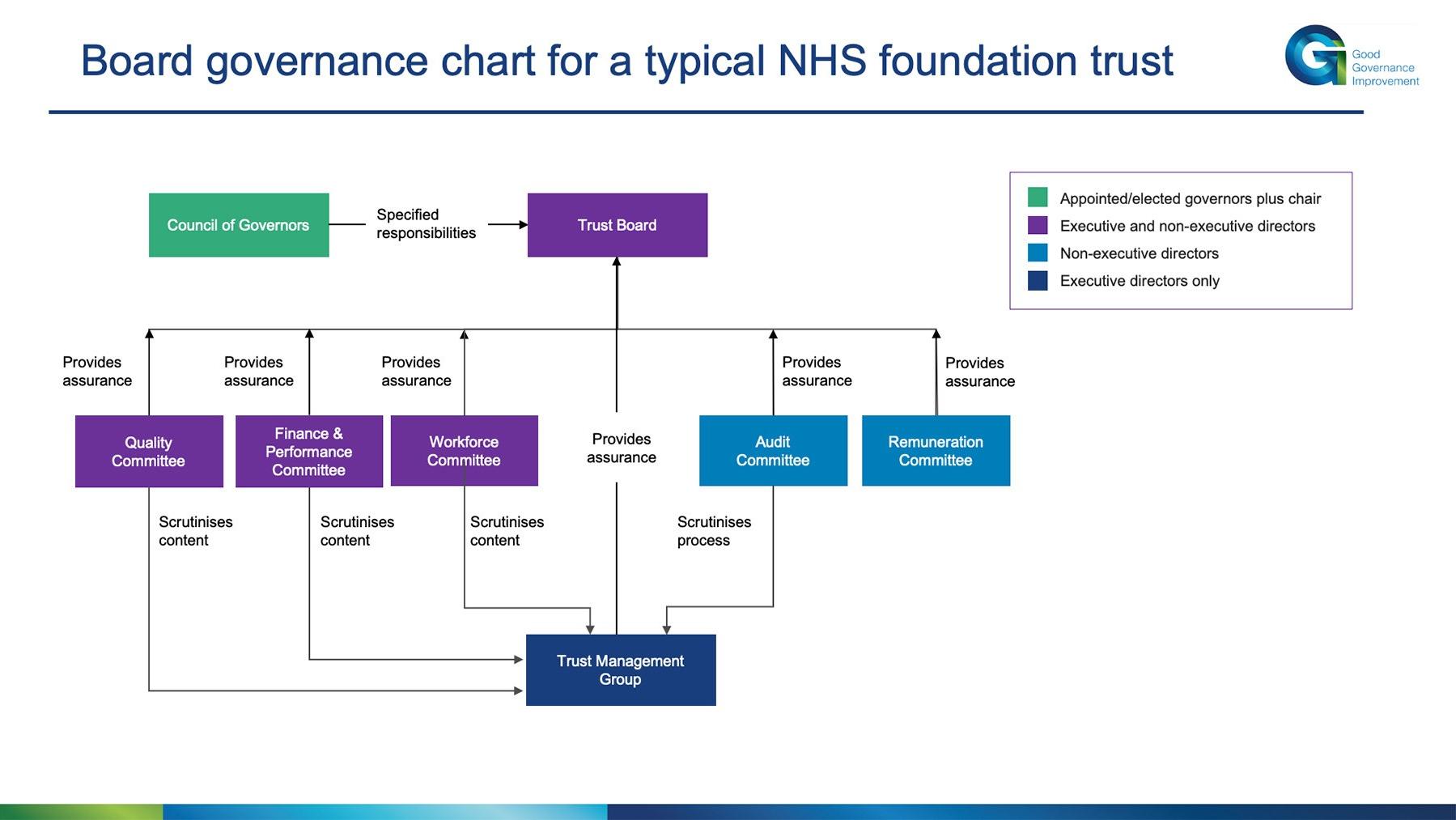

Board members need to know where their assurance comes from. In larger organisations boards have a committee structure that includes an audit committee tasked with assuring the board around governance processes, and subject matter committees (finance, quality, people, etc) to look at content.

These board committees hold specific delegations, often described in the governing document and always in the terms of reference, and in NHS organisations at least the assurances the board is seeking should be specifically identified in a board assurance framework (BAF). This is the basic means by which boards organise the assurance part of their role. So far so good.

Not all accountabilities within an organisation lie with the board. Public sector organisations have accountable (or accounting) officers who have specific responsibilities around running systems of control, and depending on which kind of public body they are these individuals are potentially answerable to Parliament for effective controls.

Other actors within public bodies, again especially the NHS, have specific accountabilities beyond the board. A good example is the medical director and their accountabilities for retained human tissues and mortuaries. Incidentally, this is why NHS board committees should always have executive as well as non-executive memberships. The executives themselves have to ‘take’ assurance because some are personally accountable, or have connected accountability, to authorities outside their own organisation. An example would be the Caldicott Guardian’s relationship with the National Data Guardian.

Public sector organisations can be convoluted too, and carry out complex work in high-risk environments every day. Increasingly, leaders understand that their work could come to the attention of the public through freedom of information requests that regularly find their way onto social media platforms.

Multiple perspectives

So what actually happens to secure assurance in large, complex public sector bodies? The managements run various assurance systems, such as for finance, information governance, quality assurance, human resources and health and safety. There is little contention that these are managerial systems accountable to the executive. Most often, multiple perspectives need to be brought together and so within managerial structures there is an architecture of the various assurance groups that structure accountability and the maintenance of the control environment.

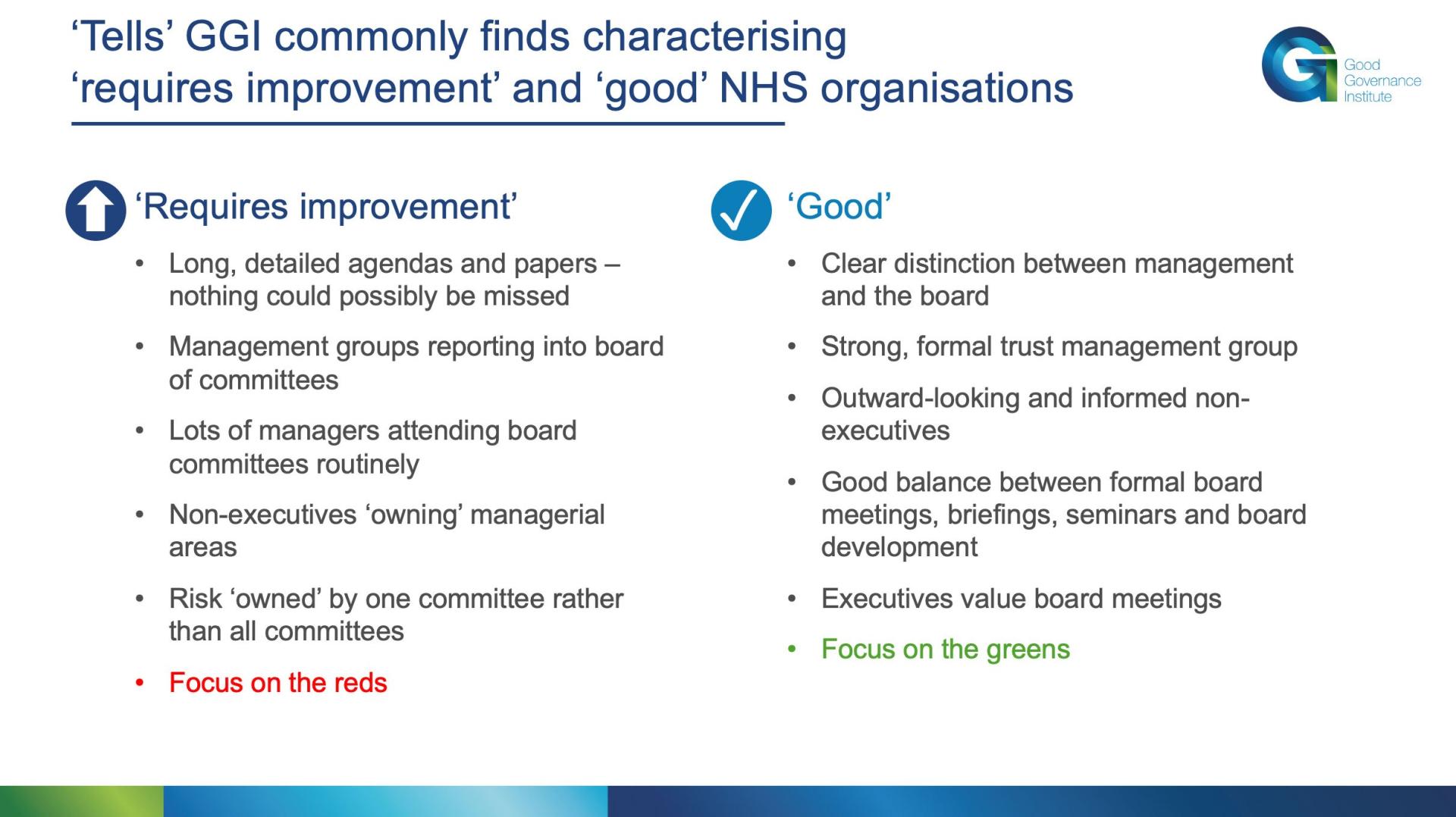

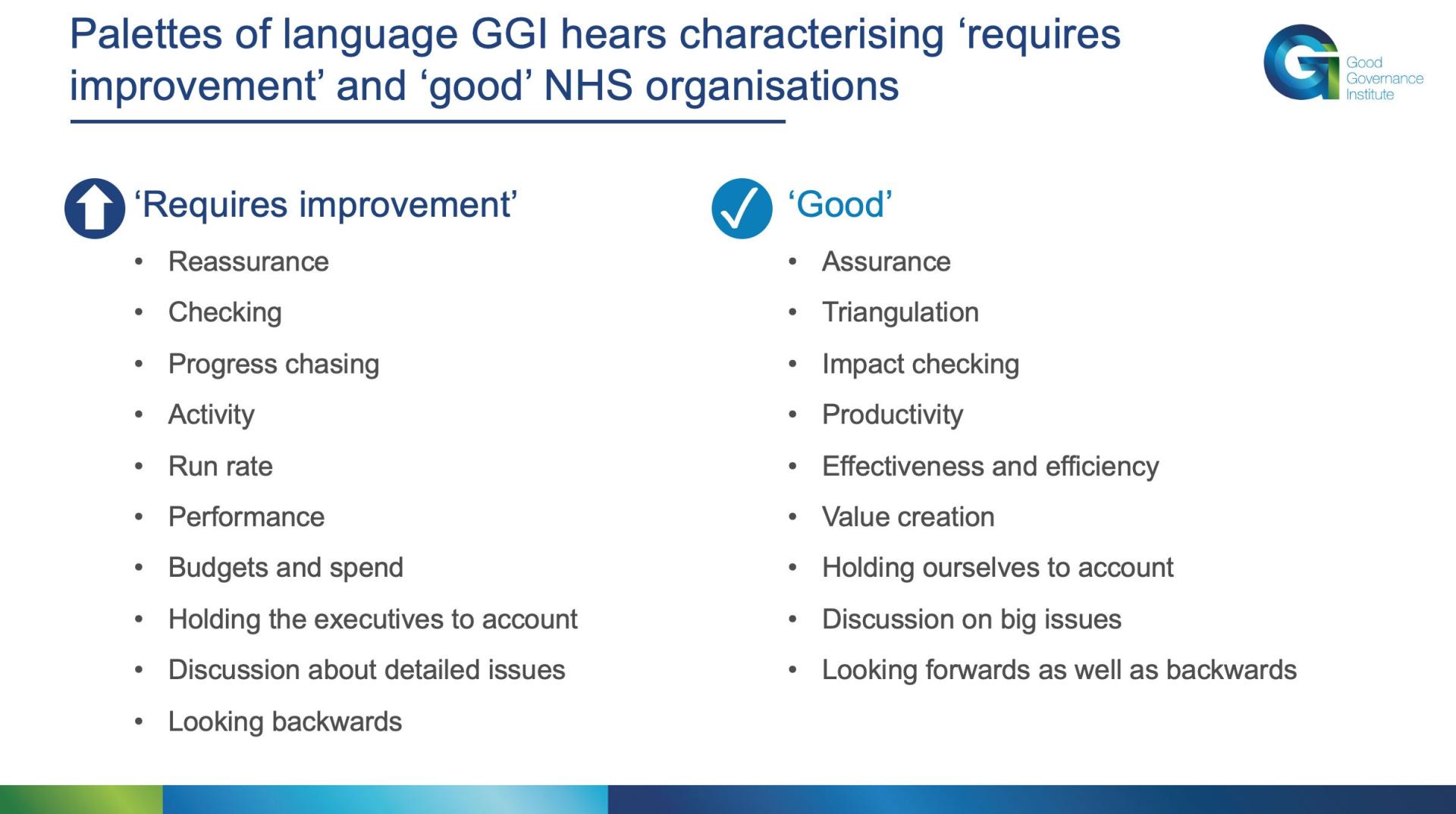

GGI has found a distinct difference in mindset between NHS organisations rated inadequate/requires improvement and good/outstanding about the role and reporting of these management groups, accompanied by different palettes of language.

More confident and mature organisations have managerial groups unambiguously reporting into the executive, and the role of the board and its committees is to scrutinise the effectiveness of this system of assurance, whereas in less well performing organisations these managerial groups will be depicted as reporting into board committees and are often referred to as ‘feeder groups’.

In other words, the pyramid of assurance meetings points to the board committee in problematic organisations, and to the accountable officer and the executive in better performing organisations.

Changing the structure is not enough

GGI shares the usual view of professional advisers, which is that it is sub-optimal governance to have management groups reporting directly into board committees. There are many reasons for this, including the following:

- Weaker control by no division of governance/management responsibilities, so no ‘second check’ on the assurance system and potential to ‘mark one’s own homework’.

- Committees not being a ‘competent’ forum to discharge primary managerial assurance. Managing by committee is never optimal.

- In safe organisations, executives should be the first to see and understand problems and are those placed to take immediate action.

- Committees not freed up to scrutinise and test areas of apparent strength – the focus is drawn those areas where issues are known about and need to be progressed thus reducing focus on how robust the actual assurance system itself is.

However, just changing the structure will not in itself improve assurance, and too rapidly reforming an organisation where custom and practice has been for board committees to manage assurance to passing this to the executive, and to assure the assurance – in other words, being sure that the system that gives you the assurance is itself sound – can lead to a collapse in control. This is because improving governance is actually an organisational development challenge every bit as much as it is a matter of plumbing.

To help understand how healthy an assurance system is, board members and senior management need to listen to how people are talking about assurance work as well as be concerned with what is happening.

Language clues

In our reviews, we look out for different palettes of language being used in an organisation and we are increasingly using simple AI tools to analyse board and committee papers as a way into the psyche of an organisation. This helps to find a possible symptom rather than evidence a definite diagnosis.

A very wise NHS leader once said ‘the board’s job isn’t to do the doing, it is to make sure the doing is done’. In highly complex organisations part of the doing is managerial assurance. It is a fundamental part of everybody’s job. In the same way that professionals of any kind are accountable for the standards operating around them so managers need to be maintaining the control environment.

The added value of the board is to test this through constructive challenge, triangulation, evaluating plausibility and seeing impact. Better control is not, of course, an end in itself, and neither is it just about the avoidance of bad things happening. Better control opens the door to value creation.

Boards can then also ask the important big questions such as ‘is our hospital safer this year than last, and will it be safer still next year?’ or ‘ are our students going to be performing better in the 2030s as a result of their study at our university?