How to make COVID-19 transformations stick

09 June 2020

One, almost universal comment on change during the first phase of the pandemic has been: “we managed to achieve things in weeks that we had failed to manage in years.” As the next phase of the pandemic unfolds, leaders are keen to retain these gains and develop them even further.

GGI believes that to do this boards need to understand that one factor that created these gains was ‘forced’ third generation quality management. This relies on changing the ‘simple rules’ to work. The pandemic did this in an unplanned instant. Should the ‘simple rules’ revert back to the pre-March conditions, then the gains will vaporise. Should they not, then organisation may face existential risks. This paper explains why.

The evolution of quality management

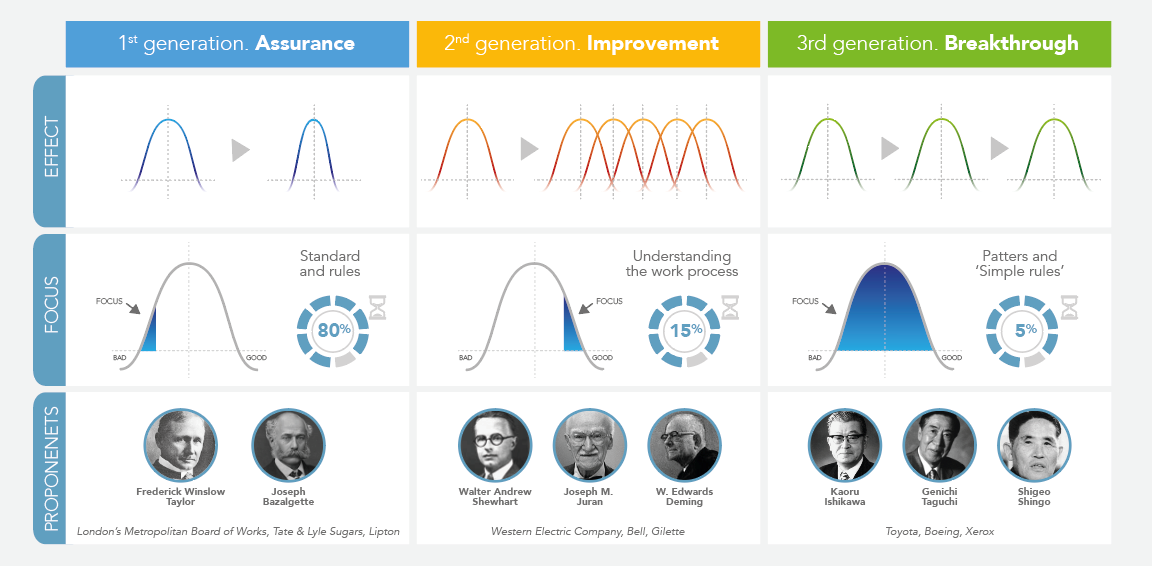

Quality management has an august history. There are many interesting examples of where standardisation or improvement methods were used, such as by Florence Nightingale at Scutari, but systematic approaches to quality management really took hold through industrialisation in the 19th century.

One colourful example often cited is Sir Joseph Bazalgette’s construction of the London sewers, which relied on the use of the notoriously unstable Portland cement. This required formal, documented and ongoing quality checking systems to ensure the cement reliably became harder in wet environments – useful in a drain.

Quality Assurance (QA)

The major force behind quality management was Frank Winslow Taylor, whose 1911 book The principles of scientific management set out first-generation quality management: quality assurance (QA). The Academy of Management voted this, in 2001, the most influential management book of the 20th century.

The premise of quality assurance is that work can be codified as a series of instructions and standards. The job of the manager is to specify these and check the workers are meeting the standards – standardisation. The job of the workers is to do what they are told.

This is a very good system if you are making a large number of identical products, such as Model T Ford cars, and gave the world reliable products to a specified and dependable quality at scale.

QA will always have its place, not least in highly regulated industries such as healthcare. However, it just standardises and removes variation. To create further improvements the managers need to design the work differently. Managers often do not have the in-depth knowledge of work design, relevant professional knowledge or team culture to do this.

Quality Improvement (QI)

Quality improvement (QI), which arose in the 1920s through pioneers such as Juran and Deming at the Hawthorne Works in Cicero, Illinois, is underpinned by the belief that those with the best knowledge of how to improve work efficiency are those that are actually doing it: the teams at the sharp end.

Improvement comes from the workers being trained to measure and analyse their work through techniques such as statistical process control, and then being empowered to redesign their work and test the effectiveness of change. The job of managers is to create the environment in which this can safely happen, expect failures as well as successes and to motivate work teams into a cycle of ongoing quality improvement. This makes ‘quality’ part of everyone’s everyday job. It is often called second generation quality management.

In healthcare we see this pioneered through the Institute of Healthcare Improvement (IHM), for example, with techniques such as LEAN or Deming’s favourite ‘Plan-Do-Study-Act’ (PDSA) cycle. QI is much better at driving waste out from processes and more suitable for services where variation and individualisation is needed, or where workers need to hold a high degree of professional knowledge. Until recently, much of healthcare worked toward second generation, QI.

Breakthrough

Third generation quality management, known as ‘breakthrough’, relies on the belief that most patterns of work can be defined by simple, but often unknown, rules. These rules have often become ritualised without any conscious understanding that they are the most significant factor in determining performance.

When starlings flock they follow two simple rules, they fly as close together as they can without hitting each other and follow the birds ahead of them as fast as they can. If you break one of these rules and reverse it (fly as far apart as you can instead of closely together, for example) you get a total change in performance and the starlings become hawks.

At a glance

Looking at a sample task, such as finding better ways of managing an overrunning meeting timetabled for an hour, what would each generation of quality management bring us?

- QA would specify that the meeting would last exactly one hour. The agenda would be timetabled by the chair and contributors would be managed to just talk to their allocated slot.

- QI would require the participants to take time out and discuss the quality of the meeting, maybe asking a participant to observe it and provide feedback. The participants would then identify strategies for managing the meeting better and set targets for meetings that lasted 70 minutes at first, with milestones of 65 mins, 60, 55 etc.

- Breakthrough would experiment with radical change to flip the meeting’s rituals. The famous example is to take away the table and chairs and the meeting then lasts ten minutes.

COVID-19

What has happened in the lockdown is that a number of the simple rules were forcibly changed. No office, no physical meetings, no working to a budget, ‘just get it done and we’ll worry about procurement later’, ‘let’s take 25% of the staff away and isolate them’, etc. This created extraordinary circumstances that took the rituals built up over decades and cocooned them.

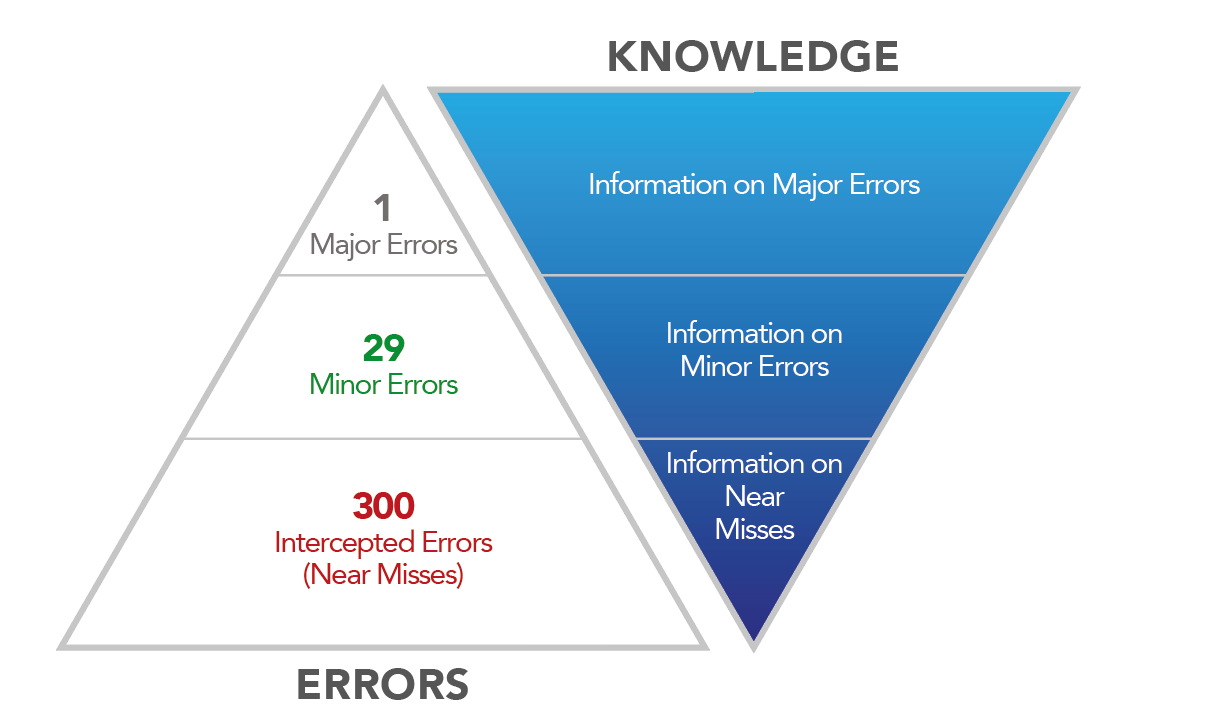

Not surprisingly, the step-change in performance was dramatic. The benefits were easy to see, while the risk and downsides were hidden in latent errors. These are just surfacing, and Heinrich’s ratio tells us that with only the major and some minor errors being immediately apparent the ocean of undetected errors and unsafe behaviours will be deep.

If teams revert to as before, then so will performance. The gains will vanish as surely as dew in the morning sun. But, if changes to the simple rules are kept, without a root cause analysis of both immediately visible errors as well as the less consequent errors that are currently undetected, then at some stage a cataclysmic error will inevitably surface.

Call to action

What boards must do, and quickly, is understand what changes to simple rules affected which elements of performance, and how deep the ocean is of unsafe behaviours and undetected errors that they are swimming in.

The job of boards is thus to support the executives as they attempt to navigate between Scylla and Charybdis.

We are keen to hear your views. If this briefing prompts any questions or comments, please call us on 07732 681120 or email advice@good-governance.org.uk

Andrew Corbett-Nolan

Chief Executive