The GGI guide to integrated care partnerships

07 February 2022

In a recent interview with GGI, Kath O’Dwyer, chief executive of St Helens Borough Council and the Liverpool City Region local authority chief executive representative on the Cheshire and Merseyside Integrated Care System (ICS), articulated a widely-held view about integrated care partnerships (ICPs) – one of the two controlling bodies of each of England’s 42 ICSs.

When the government announced that there would be integrated care boards focused on NHS statutory responsibilities, Kath noticed a change in perception. She said: “That felt like a bit of a shift, resulting in a bit more political and partner suspicion, with people thinking ‘well actually, is that the board that's going to make all the decisions and decide about the money and decide about anything that matters? Will the partnership board just be a talking shop, and what powers is it going to have? How is it going to make a difference – will it really be doing things differently to deliver true integration and address long standing health inequalities?”

These suspicions persist – and yet the implementation deadline approaches. The need to understand, and get on with establishing and developing, integrated care partnerships (ICPs) has become a pressing issue for three reasons:

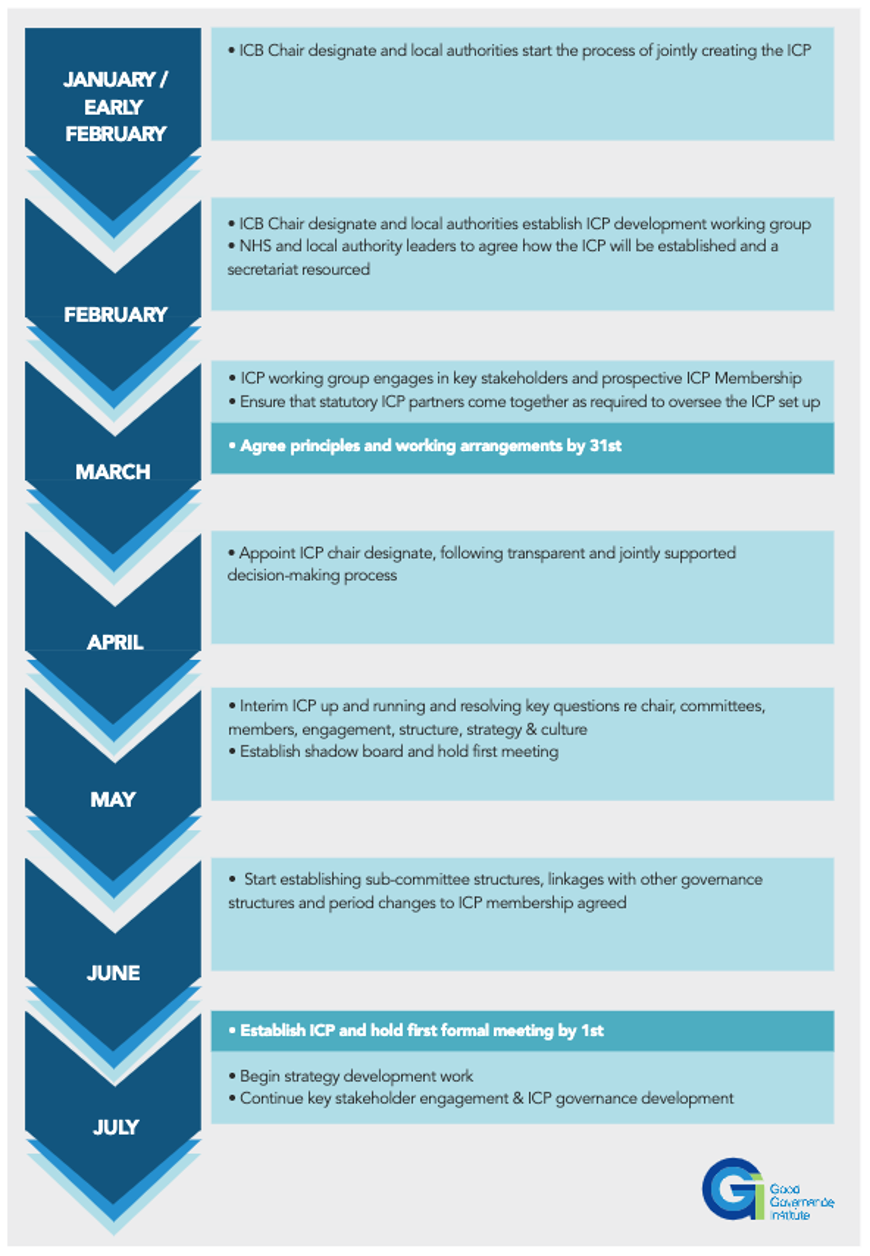

- ICP timeline: The integrated care partnership engagement document, published on 15 September, tasked all NHS Integrated Care Board (ICB) chairs designate to ensure that ICPs are established and provided a timetable of steps (now out of date and due to be updated), with an expectation of an immediate start. Despite the additional time, all ICSs need to be getting on with establishing their ICPs with principles agreed by 31 March and the ICP established by 1 July.

- ICB submissions: Developing the system. As the constituent parts of integrated care systems are inter-related, due attention and development needs applying to the ICP alongside that given to the ICB, as well as other key ICS entities.

- Engagement: Engagement and relationship development/ management is a significant part of developing the ICP and needs the appropriate time and focus to be done in a planned and effective way.

Following on from our article on integrated care boards, this article sets out:

- ICP development timeline and local authority (and other key partner) engagement

- ICP key early decisions

- ICP longer-term strategy development.

At the end of the article, you will find a GGI ‘cheat sheet’ on ICPs, which provides a compact summary of the guidance for ICPs regarding purpose, role, membership, chair, accountabilities, structure, operating model and meetings.

ICP development timeline and local authority engagement

As the ICP needs to be jointly established by the ICB and local authorities, it cannot be officially established until after the ICB becomes a statutory body in July 2022. Nonetheless, the guidance expects that all ICSs will have an ICP up and running in by 1 July 2022, with at least a chair and a committee of the statutory bodies (ICB and local authorities).

The guidance tasks the ICB chair designate with ensuring that key milestones in the establishment of the ICP are achieved. At the time of the guidance document’s publication (15 September 2021), the first milestones were set for September, October and November of last year. These have now moved on with the official push back of the timeline. Despite the additional time, there is a clear expectation of immediate action.

Revised ICP outline establishment timeline

The initial timeline from the September guidance sets a critical path for ICP establishment through a number of ‘practical steps’:

We now ask all 42 integrated care systems to take the following five steps (please note the indicative dates). We ask the NHS ICB Chairs Designate to ensure these steps are carried out in their system, in partnership with local government.

- Recognise that it is for the NHS and Local Authoritys (LAs) – as the statutory partners in each ICS – to start the process jointly of creating an ICP in preparation for legislation (September 2021)

- Reach agreement between NHS and local authority leaders as to how the ICP will be established and a secretariat resourced, at least during the 2021/22 transition year (October 2021)

- Ensure that the statutory ICP partners come together as required to oversee ICP set up, including engagement with stakeholders (November 2021)

- Appoint an ICP chair designate, taking account of national guidance on functions and ensuring there is a transparent and jointly supported decision-making process (February 2022)

- Determine key questions to be resolved for that particular system including but not limited to the following (April 2022):

- What kind of chair would best galvanise the system behind its common aims and what is the process for appointment?

- Who might constitute an ICP committee that might galvanise the ICS and how should those individuals be chosen?

- What would be required to deliver an inclusive approach to engagement, in terms of methods, resourcing, and public reporting?

- To what extent can existing structures be used or adapted to create the ICP so as to build on what happens already?

- To what extent do existing ICS plans meet the requirement for a health and care strategy and how might they be refreshed?

- How might the ICP meet the ten principles described in NHSEI’s ICS Design Framework to set the culture of the system?

The outline critical path timeline below provides a suggested update to the September guidance in light of the July pushback, with specific deadlines emphasised.

ICSs that haven’t started this work would be well advised to do so soon. There is a clear expectation that conversations between the NHS and local authorities should be initiated as soon as possible. The top topics for discussion, laid out in the guidance, include seeking agreement on:

- ICB membership and constitution

- membership of the ICP

- how the ICP will be resourced, e.g. for the necessary secretariat and other functions

- arrangements for input to the ICP from - directors of public health, representatives of adult and children’s social services – for example by at least one director of adult social services or director of children’s services, relevant representation from other local experts, through Health and Wellbeing Board (HWB) chairs, primary or community care representatives and other professional leads, for example in social work and occupational therapy.

ICP key early decisions

GGI’s work with ICS leaders shows that discussions with partners on developing an effective ICP, should focus their early attention on six things:

1. Establishing principles

Discussions can get entrenched if partners are in the mindset of representing their organisation’s or sector’s interests. A key to unlocking this dynamic is to start by aligning everyone around principles. The ICS design framework lays out suggested ICS principles, which include subsidiarity, distributed leadership, collaborative working, and continuous learning. Many ICSs adopt these, sometimes with local adaptations. We suggest supplementing these with governance design principles, such as avoiding duplication, clarity of purpose and roles, and alignment with strategic objectives.

2. Establishing clarity of roles

There is a widespread misinterpretation of the role of ICS entities, such as the ICP and ICB, with many regarding the roles as being ‘representative.’ The guidance is explicit that members of the ICS, including board members of the ICP and ICB, are to act in the interests of the ICS population, not of another organisation to which they may belong. Their sector knowledge should be used to inform decisions, not represent particular interests. Achieving a common understanding of this also helps navigate away from suggestions of creating complex sub-structures for gaining consensus among sub-groups.

3. Adopting a systems view

Initial plans in some ICSs showed a lot of overlap and duplication between the suggested membership of the ICB and ICP, which risks the same decisions being discussed by the same people in different fora. Taking a ‘system view’ and creating some cross-cutting views, which show memberships of different groups side by side, can help identify and resolve potential issues of duplication.

4. Defining a lean ICP

A lean ICP that respects the principles of subsidiarity should have no more than 25 members. We have heard of proposed memberships of up to 60 people, which will prove to be unwieldy and ineffective. The guidance is explicit that the membership of the ICP should be kept to a ‘productive level’. It suggests several alternative ways of gathering input from a wide range of stakeholders, including the use of sub-groups, panels and dedicated workshops.

5. Considering joint chairs

The guidance allows for the chair of the ICP to be the same or separate from the ICB chair. One benefit of the ICB chair also chairing the ICP is that part of their role is to develop the relationship between the groups, and communicate the views of the ICP to the ICB. The potential benefit of having separate chairs is that it creates room for more democratic representation.

6. Commissioning joint ICB and ICP development programmes

Successful ICSs need to be built on systems leadership and systems mindsets. This is very different from the Clinical Commissioning Group world. Leading ICSs are commissioning joint systems board development programmes to establish the required culture and behaviours.

ICP longer term strategy development

Developing the integrated care strategy is recognised as being a longer-term iterative process, which needs to build on strategies at place, and strategies developed by the health and wellbeing boards. Further guidance of the content of the integrated care strategy is likely. Initial guidance is that it should focus on:

- a shared vision and purpose for ICS partners

- integrated provision

- integrated records

- integrated strategic plans

- integrated commissioning of services

- integrated budgets

- integrated data sets

As the strategy is developed, it would be helpful to establish the relative roles of the ICP, ICB, HWB, Place Based Partnership (PBP), the ICS executive, and others as appropriate, in the annual planning cycle. It would also be advisable to agree how potential disagreements or conflicts are resolved.

The Good Governance Institute is playing a leading role in the development of integrated care systems. We have worked directly with a third of ICSs and indirectly with them all and so have excellent insights into best practices across England. Our international work brings insights from integrated people-centred care systems around the world. If you would like to learn more about our experiences, or to discuss a particular issue you are facing, please call or email us.

Fenella McVey: 07732 681128, fenella.mcvey@good-governance.org.uk

Mason Fitzgerald: 07732 681120, mason.fitzgerald@good-governance.org.uk

The GGI cheat sheet on integrated care partnerships (ICPs)

Expectations regarding ICPs are laid out in two key guidance papers:

- ICS design framework (June 2021)

- Integrated care partnership engagement document (updated on 20 September 2021), which was developed by the Department for Health and Social Care (DHSC), NHS England and Improvement, and the Local Government Association (LGA).

The expectations on purpose, role, membership, chair, accountabilities, structure, operating model, and meetings are described below.

Purpose: To align the ambition, purpose and strategies of partners across the system to integrated care and improve the health and wellbeing outcomes for their population

Role – The role is expected to encompass the following:

- Develop an ‘integrated care strategy’ for its whole population (unless the use of the HWB or other strategy is agreed)

- Using best available evidence and data, covering health and social care (both children’s and adults’ social care)

- Built bottom-up from local assessments of needs and assets identified at place level, based on joint strategic needs assessments

- Focused on health and social care outcomes, reducing inequalities and addressing the consequences of the pandemic for communities

- Having regard to the NHSEI Mandate and any guidance issued by DHSC, and explicitly covering the issue of integration and the use of Section 75 arrangements, including pooled funds

- Considering a joint workforce plan, including the NHS, local government, social care and VSCE

- Considering mobilising assets beyond anchor institution boundaries

- Forming strategies which are ambitious and challenging and enable integration and innovation

- Facilitate joint action to improve health and care services and to influence the wider determinants of health and broader social and economic development

- Champion inclusion and transparency

- Challenge all partners to demonstrate progress in reducing inequalities and improving outcomes

- Support place and neighbourhood-level engagement ensuring the system is connected to the needs of every community it includes

- Convene, influence and engage the public and communicate to stakeholders in clear and inclusive language

Membership: The membership is expected to be a broad alliance of organisations and representatives concerned with improving the care, health and wellbeing of the population.

The following are required members:

- Local authorities who are responsible for social care services in the ICS area (with a duty to co-operate)

- An ICB representative (with a duty to co-operate)

Other members should be agreed by ICB, local government and other partners.

It is emphasised that not all partners need be members of the ICP and that membership should be kept to a productive level.

It is expected that sub-groups, networks, dedicated workshops and other methods to be used for broader stakeholder participation and to include views and needs of patients, carers, the social care sector.

Stakeholders who must be involved, but not necessarily as members, include:

- Health and wellbeing boards

- Other statutory organisations

- Voluntary, community and social enterprise (VCSE) sector partners

- Social care providers and organisation with a relevant wider interest, e.g. employers, housing, education providers, criminal justice system

- Local authority directors of public health to support, inform and guide approaches to population health management and improvement

- Local Healthwatch organisations to advise on engagement and scrutiny

- Clinical and professional leadership (including primary, community and secondary care) to ensure a strong understanding of local needs and opportunities to innovate in health improvement

- Input from representatives of adult and children’s social services – for example by at least one director of adult social services or director of children’s services

- Relevant representation from other local experts, through HWB chairs, primary or community care representatives and other professional leads, for example in social work and occupational therapy

It is expected that membership may change as the priorities of the partnership evolve.

In smaller systems, the ICP and HWB may have the same membership and organise to streamline their meetings.

Chair: ICB and local authorities are to jointly select the ICP chair and define their role, term of office and accountabilities. The ICP and ICB and ICP chairs could be separate or the same – it is noted that separate chairs may help democratic representation, while the same chair may help co-ordination

Selection criteria for the ICP chair include: able to build and foster strong relationships in the system, collaborative leadership style, committed to innovation and transformation, expert in delivery of health and care outcomes, able to influence and drive delivery and change.

There is no prescribed appointment process or remuneration.

Accountabilities – The guidance sets out the following accountabilities:

- The ICB and local authorities must have regard to the ICP strategy when making decisions, commissioning or delivery services

- As members of the ICP, he ICB, local government and other stakeholders responsible for delivering the priorities of the ICP, will be able to hold each other to account

- ICBs, LAs and other partners should share intelligence with the ICP in a timely manner to ensure the evolving needs of the local health service are widely understood and opportunities for at scale collaboration are maximised

- ICSs (both the ICB and the ICP) will be required to take account of HWB strategies and Joint Strategic Needs Assessment (JSNA) in developing their plans, to avoid duplication of effort

Structure – The ICP structure is required to be:

- A ‘forum’ to bring partners – local government, the NHS and others – together across the ICS

- A statutory committee, established by the NHS and local government as equal partners (Note that the ICP is not a statutory body and does not take on functions from other parts of the system)

- Evolved from existing arrangements and with mutual agreement on its terms of reference, membership, ways of operating and administration (arrangements will vary by size and scale of the system)

Operating model: The operating model is not prescribed. ICPs can develop the partnership arrangements that work best for them, based on equal partnership across health and local government, subsidiarity, collaboration and flexibility. There are, however, expectations that mechanisms (e.g. citizens panels, co-production) are in place for ensuring strategies are developed with people with lived experience of health and care services and communities, e.g. patients, service users, unpaid carers, under-represented groups.

Meetings: Formal sessions are expected to be held in public.