Why stewardship is important now

29 June 2020

The form of governance advocated by the Good Governance Institute (GGI) has always relied heavily on the concept of stewardship – a word that has its origins in the Anglo-Saxon ‘stig weard’ or ‘keeper of the hall’.

GGI explains stewardship through the image of a ninth century village, somewhere in the Midlands perhaps, where the most important building would be the communal hall. Here, justice would be dispensed, sagas told, feasting and celebrations of important moments held. The hall would also offer protection in difficult times. The keeper of the hall was the guardian of community property.

Drawing from this concept, GGI defines stewardship as being accountable for something that you do not own which is valuable to the community, and then passing it on to the next custodians in a better state than you took it on. To us, stewardship is the key word to describe the governance duties of a director in a modern enterprise.

Corporate stewardship

Other governance authorities, particularly those active within the corporate sector, see stewardship as something distinct from the role of the board. In their lexicon, stewards are those responsible for major investors or shareholders, who should be diligent stakeholders in an enterprise and concerned with holding the board to account for the investment they have made, on behalf of – and in the interests of – others.

This broader concept of stewardship, intertwined but separate to the board, is captured in various public sector concepts such as antimicrobial stewardship, which is the systematic effort to educate and persuade prescribers of antimicrobials to follow evidence-based prescribing, in order to stem antibiotic overuse, and thus antimicrobial resistance.

Another example would be environmental stewardship, which refers to the responsible use and protection of the natural environment through conservation and sustainable practices. As long ago as 1949 the American ecologist Aldo Leopold championed environmental stewardship based on a land ethic of ‘dealing with man's relation to land and to the animals and plants which grow upon it.

In their article in the Harvard Business Review of February 2020, the leading American corporate advisors O’Kelley and Neal encouraged boards to look forward and not back. As stewards, boards were not markers of their own enterprise’s homework. They explained that: “Reviewing financial statements, audit activities, and compliance activities are the responsibility of the board, not the mission of the board.” They pointed out that: “The most important — and most impactful — activities are forward-looking ones: strategic planning, CEO and management succession planning, and improved oversight of enterprise risk and mergers and acquisitions transactions. These activities help the company create its future.”[2]

NHS boards

GGI feels there are lessons for NHS boards in this, and in the corporate interpretation of stewardship, for systems working where boards are needing to go beyond their immediate fiduciary and regulatory duties in the interests of the broader range of stakeholders.

NHS provider boards need to think in terms of responsibility for population health and the sustainability agenda in all its manifestations. This in turn requires public sector boards to have an ambition that is much greater than a return to stasis. But how do boards actually change how they work, given that in legal terms there is no change whatever to their current duties?

GGI encourages boards not to minimise this task, nor leave things to settle naturally. In the coming weeks our bulletins will include further specific approaches to how boards can navigate their way through the coming year but an essential starting point is for the board to settle on a single mindset to guide the way this task is approached. This is not to iron out differences of opinion or diminish constructive challenge, but rather to agree as a whole board team the change in context within which the board operates – and perhaps to be more guided by the principles of stewardship and less by the regulation rule book.

Apply and explain, not comply or explain

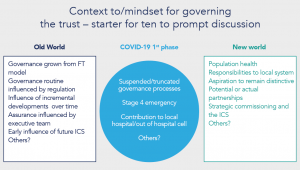

Changes in context for an NHS organisation might start to look like this:

GGI would argue that getting to one mindset around context and then next steps frees up the board to agree how the principles of good governance need to work in practice, and then to apply these and explain the rationale to stakeholders.

This moves us on from the current dynamic of having to accept, in an unthoughtful way, the centre’s requirements as delivered, and then explain any differences. So apply and explain rather than comply or explain.

Broadening out the concept of stewardship from either GGI’s interpretation or the corporate world’s emphasis on stewardship as something applied externally towards a board, by bringing the two together, starts to build a consensus that helps systems-working.

The mindset should be that, as board members who are also – within the NHS – holders of public office, the main duty is to citizens and communities rather than individual organisations. Stewardship keeps us focused on the ideas of both being a transitory caretaker but also the duty, eventually, to hand on accountability to others in an improved state.

Broadening this out now to adopt nuance on stewardship from the corporate world is to accept the responsibility to ensure that colleague organisations, in this new world responsible for delivering this joint mission successfully, are themselves team-players and also embrace good governance in how they work.

Next steps

As stated, in the coming weeks GGI’s bulletins will include practical examples of how NHS boards can work through understanding the new context and how they can develop to step up as holders of public office – ultimately to be held to account around matters of public, rather than a single-entity, interest.

In the meantime, we would invite boards to consider the following points.

- The stewardship approach helps us deliver systems-working in a way that doesn’t forget that, at present, the fiduciary and regulatory responsibilities of directors have not changed.

- Expanding stewardship thinking to include how stewardship is understood in the corporate world helps the public sector at this complex time.

- Understanding changes to the context the board is working in is not a trivial exercise, but it is essential to allow the board to adopt the mindset that will enable partnerships and systems working.

- This allows boards to use, in a practical way, good governance to achieve meaningful outcomes, rather than be held back by rules that belong to a previous decade.

If this bulletin prompts any questions or comments, please call us on 07732 681120 or email advice@good-governance.org.uk

[1] Leopold, Aldo; ‘A Sand County Almanac’, Oxford University Press, 1949

[2] O’Kelley, Rusty III and Neal PJ; ‘Top Boards Do these Four Things Differently”; Harvard Business Review, Boston February 2020

Andrew Corbett-Nolan

Chief Executive